Forestalling an existential threat

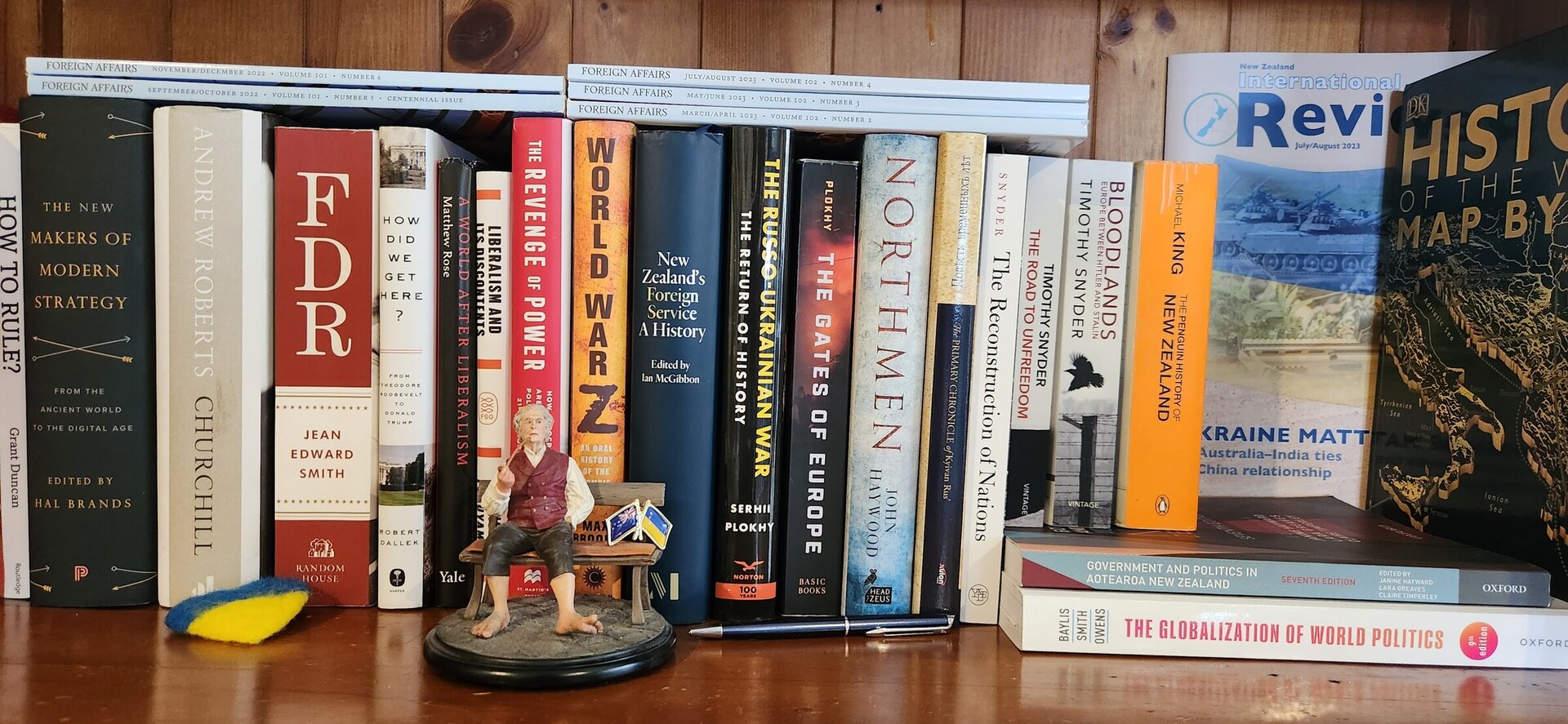

The original essay was written in March 2023, expanded in July and first published as an article titled "Forestalling an existential threat" in the November/December 2023 issue of the New Zealand International Review

The primary causes of the wars in Georgia and in Ukraine have been long-standing imperial ambitions of Russia being greedy for power and dominance, undermining the sovereignty and self-determination of smaller states, aiming to redraw national borders to control at least as much as it once did, heedless about lives and human rights; spreading disinformation. Architects and executives of the contemporary world order bear their share of responsibility for letting it all happen. In the end, the chain of wars, if triggered by these two, may result in the collapse of the existing world order.