The full article titled "The problem of war" was first published in the January/February 2024 (Vol.49#1) issue of the New Zealand International Review

The most popular theories of political strategy nowadays are still political realism and liberal internationalism. When trying to explain state aggression, over centuries, political realists have developed a message that wars are always driven by a mix of personal and state self-interest, and hence ineradicable. Liberal internationalists, on the contrary, keep trying to abolish state aggression as a continuation of state politics by evolving the framework of global institutions, common law, and collective security, although not very successfully so far. Today, the former promote isolationism and appeasement, while latter – alliances and armament.

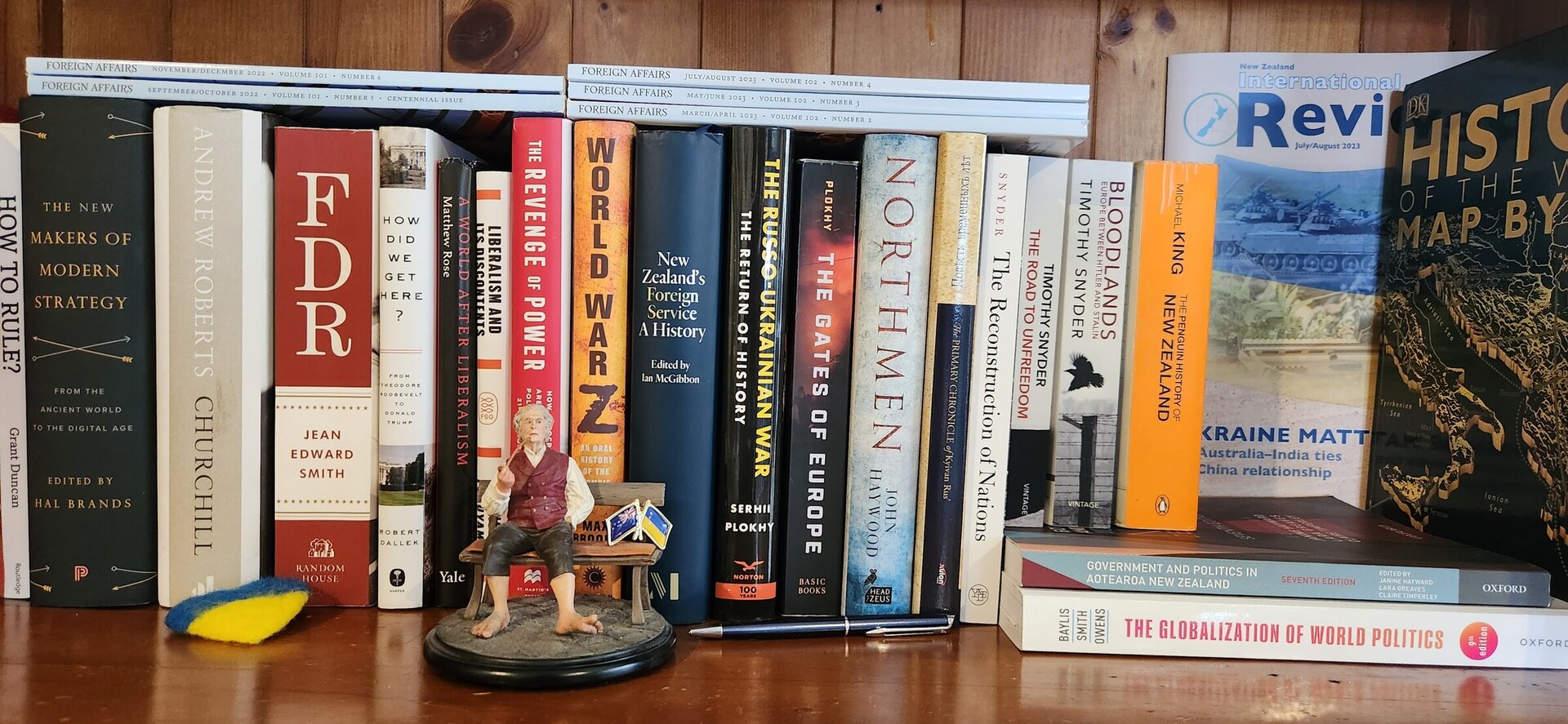

Image source: another issue of the New Zealand International Review.